GARY DORNING/POSAUNE

A Lifeline From the Philippines

Darkness was engulfing Europe. By 1938 Adolf Hitler had been leading Germany for five years, and his Nazi government was casting a sinister shadow over the Continent—especially over Jewish people.

Hitler had kicked Jews out of German and Austrian schools, excluded them from many professions, and stripped their citizenship. The Nazis were invading Jewish homes, smashing their businesses, and burning their synagogues. Daily Jewish life had become a nightmare. Still, rumors were circulating that Hitler had a final plan for them that was still far more evil.

Many Jews realized that their best hope was to escape the country. They tried to relocate to other nations, but almost none of them, including even the United States, would ease their immigration restrictions and let them in.

The situation was looking darker and darker.

Half a world away from Germany, news about the Nazis’ diabolical plan came up during a game of poker.

A Royal Flush

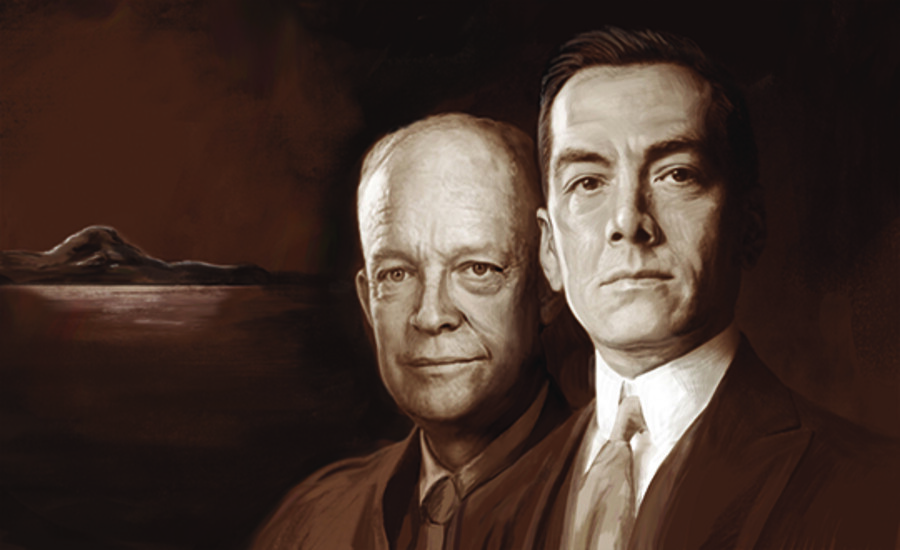

At a table in the Malacañang Palace in Manila, Philippines, sat Manuel L. Quezon, the first president of the Philippine Commonwealth, U.S. military adviser Col. Dwight D. Eisenhower, U.S. High Commissioner to the Philippines Paul McNutt, and Alex and Herbert Frieder, Jewish-American brothers living in the Philippine capital where they ran a cigar factory. But the Frieders were more than just tobacco tycoons.

“[T]he Frieder brothers were also the head of the Jewish Refugee Committee in Manila,” writer and film director Matthew Rosen told the Trumpet. “And they had a secret telegram sent to them from Austria from the Chinese ambassador there, saying that he had heard rumors that the Jews were going to be rounded up and put into death camps.”

So during this poker game, the Frieders brought the troubling report up with President Quezon and the American officials. The brothers were unsure how the group would receive the news, but the response was precisely what they had hoped for. Rosen, who recounts this history in his 2018 film Quezon’s Game, said, “Together, they agreed that they had to, in some way, save as many of these Jews as they possibly could.”

President Quezon in particular was all in.

‘A Bigger Project Than Palestine’

Quezon determined to make his nation one of the first to publicly give safe haven to Jewish refugees. But it was clear from the start that it would be an extraordinarily difficult and risky undertaking. This was partly because many in Quezon’s own cabinet opposed the idea due to anti-Semitism. Alex Frieder wrote that such men saw Jews as “Communists” and “schemers” out to “own the Philippines.”

Defying these powerful men came with risks for Quezon’s political career. But he stood up to each of them and made them feel, in Frieder’s words, “ashamed of themselves for being a victim of propaganda intended to further victimize an already persecuted people.”

More difficulties were presented by the need for each Jew to obtain both an exit permit from Berlin and an entry permit for Manila.

Hitler must have reasoned, at least at this point, that paper for visas was cheaper than poison gas, so the Nazi government granted the necessary exit documents for many Jews. But it was the entry permits that were a problem. The Philippines was a semi-independent commonwealth under control of the United States and its immigration laws. The U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 said the country “took no official cognizance of refugees and thus made no provision for offering asylum to the victims of religious or political persecution.”

Despite the rise of Nazi Germany, this law had not been modified.

U.S. policy let the Philippines issue only a couple hundred entry permits each year—a mere fraction of the number Quezon wanted to help.

In a letter dated Dec. 8, 1938, Herbert Frieder said Quezon “heartily approved” of a plan to open the Philippine island of Mindanao up to basically as many Jews as wished to come. “He was willing to give them all the land that they wanted, build roads for them, and do everything in his power so that they could reestablish themselves,” Frieder wrote. “[H]e would be happy if we could settle a million refugees in Mindanao.” This would be “a bigger project than Palestine.”

Quezon understood that pushing so boldly against U.S. law could bring his career and even his nation’s standing with America into question. And he understood that as war drums were pounding around the world, the Philippines faced major troubles of its own. But he believed the plight of the Jews was more pressing than any of that. And he came to see it as a moral obligation to help them at all costs.

“In that time of real darkness,” Rosen said, “when everybody was saying, We’ve got our own problems, he showed that every life was important.”

Help Wanted

Back in Europe, rage against Jews was intensifying. By the start of 1939, tens of thousands had already been forced into concentration camps, and those still free were finding it more and more difficult to work or even obtain food because other Germans refused to sell to them.

As Quezon learned of these horrors, his work to bring Jews into the Philippines took on greater urgency.

By the time his plan was formalized, he had set the number of Jews that he sought to help—at least in the first wave—down to a more realistic 10,000. At his behest, Eisenhower and McNutt went to work persuading U.S. Senators to grant the desired number of visas.

There was also a question of funding. One part of American immigration law stipulated that no person likely to become a “public charge” or a burden on the economy could immigrate to U.S. territory.

So the Frieders—Alex, Herbert and their other three brothers, Morris, Phillip and Henry—went into overdrive throughout much of 1939 raising funds, mainly among American Jews, to support the European refugees. They also placed a series of “help wanted” ads in German newspapers asking Jews with specific skill sets to relocate. One such notice listed: “20 Physicians, 10 Chemical Engineers, 25 Registered Nurses, 5 Dentists, 2 Ortho-Dentists, 4 Oculists, 10 Auto Mechanics, 5 Cigar and Tobacco Experts, 5 Women Dressmakers, 5 Barbers, 5 Accountants, 5 Film and Photograph Experts, 1 Rabbi, 20 Farmers.”

Applications began pouring in. By the end of the year, each steamer arriving from Europe brought a few Jewish families to the tropical island chain where they would restart their lives.

In March 1940, as the Jewish numbers grew, Quezon donated several acres of his own land in Manila to refugee families—just in time for them to observe the Jewish holiday of Purim there. In July, he issued a presidential decree stating that “every inhabitant of the Philippines” should “cooperate in extending whatever aid may be necessary for the safety and care of these refugees.”

“It is my hope, and indeed my expectation,” Quezon said, “that the people of the Philippines will have in the future every reason to be glad that when the time of need came, their country was willing to extend a hand of welcome.”

Meanwhile, he and the Frieders kept working toward a deal to open Mindanao to a larger number of refugees. They conducted exhaustive land surveys, and lobbied dozens of politicians, and on Nov. 21, 1941, they scored a major victory: signing the final contract for the purchase of a massive tract of land on the island.

It looked like the way was opened for thousands and thousands of European Jews to get free of the Nazis and start over in the Philippines.

But 10 days later, the situation dramatically changed.

Japanese Occupation

On the morning of Dec, 7, 1941, Imperial Japan attacked the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Hawaii. Ten hours later, the Japanese began a sneak attack on the Philippines and occupied the nation.

Japan’s conquest forced America’s Asiatic Fleet in the Philippines to withdraw to Indonesia, devastated the Philippine economy, and unleashed waves of hunger and disease which along with Japanese bullets and bayonets killed half a million Filipinos. It also destroyed Quezon’s attempt to save 10,000 Jewish lives.

But before the Japanese arrived, he and the others helping the cause had been able to throw a lifeline to some 1,300 Jews.

These were individuals who otherwise almost certainly would have been rounded up by Nazis, forced into deplorable concentration camps, and murdered—either slowly by backbreaking toil and starvation, or quickly in gas chambers.

Some 1,300 people were plucked out of that fire by President Manuel Quezon.

Despite the fall of the Philippines, during and after the war these Jews formed what became a thriving community in Manila. In 2017, the Israeli embassy in the Philippines estimated that there are now about 8,000 descendants of the refugees Quezon saved.

“It’s a remarkable story,” Rosen said, “about a remarkable feat of humanity.”

Would You Be a Quezon?

Manuel Quezon was a devout Catholic. He faced the same pressure that Catholics around the world faced in the lead up to and during the Holocaust to turn a blind eye to the horrors Nazi Germany was committing against Jews, and to perhaps even take some satisfaction in it.

The head of the Catholic Church throughout World War ii, Pope Pius xii, chose not to condemn the Nazi slaughter of Jews. Instead he quietly helped the genocide. “[Pius] betrayed an undeniable antipathy toward the Jews” and drew “the Catholic Church into complicity with the darkest forces of the era” Roman Catholic historian John Cornwell wrote in his 1999 book Hitler’s Pope. Even after the war, when the full evil of the Nazi genocide was known, the Roman Catholic Church helped the worst Nazi perpetrators escape to sunny refuges of their own in South America.

Pius was head of the Church that Quezon devoutly followed. Yet instead of buying into the anti-Semitism that consumed so many minds during that dark time, Quezon confronted those harboring that toxic view, and risked a great deal to help those in need—at a time when so few would.

Quezon refused to remain silent in the face of what he knew was wrong. He refused to sit idly by as evil was being wrought. He obeyed his principles and his God. And in so doing, Manuel Quezon gave an example to those who worship the true God: Even when the world is insisting that we go along with its evil, as the Apostle Peter said in Acts 5:29, “We ought to obey God rather than men.”